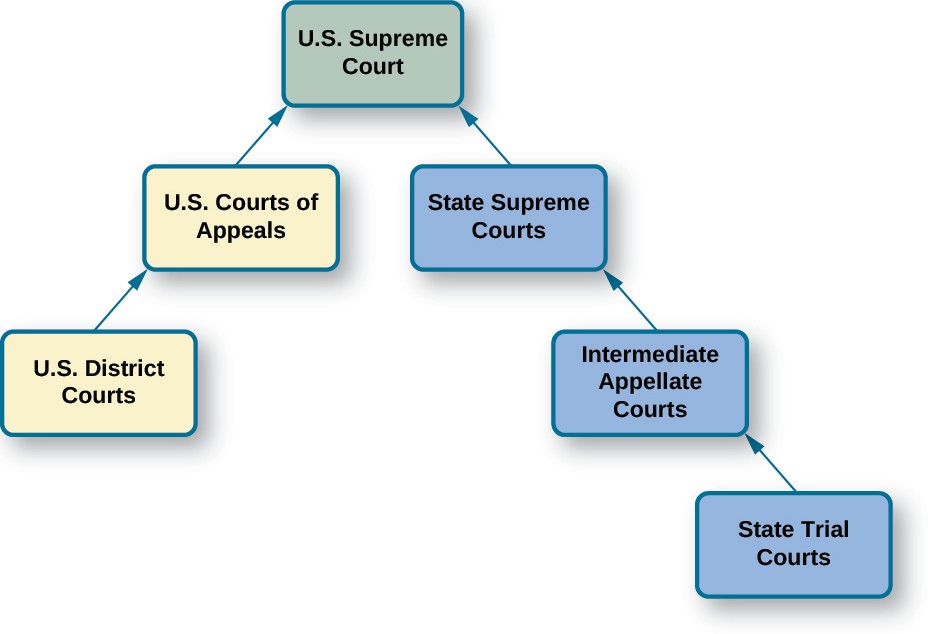

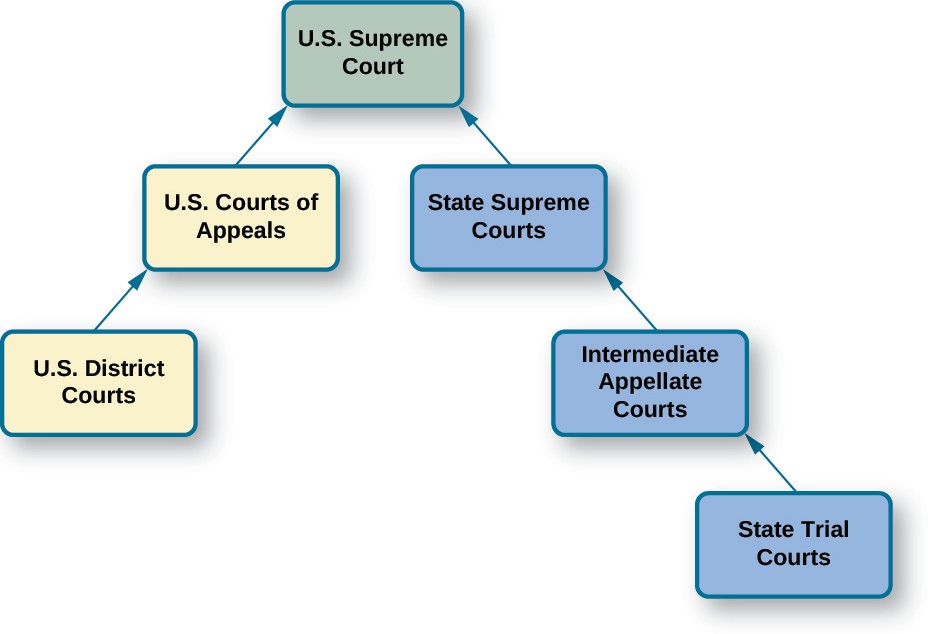

Before the writing of the U.S. Constitution and the establishment of the permanent national judiciary under Article III, the states had courts. Each of the thirteen colonies had also had its own courts, based on the British common law model. The judiciary today continues as a dual court system, with courts at both the national and state levels. Both levels have three basic tiers consisting of trial courts, appellate courts, and finally courts of last resort, typically called supreme courts, at the top. However, the District of Columbia and 10 states do not have an intermediate court of appeals. The ten states are: Delaware, Maine, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming. The other 40 states follow the three-tier court system pattern of the national government.

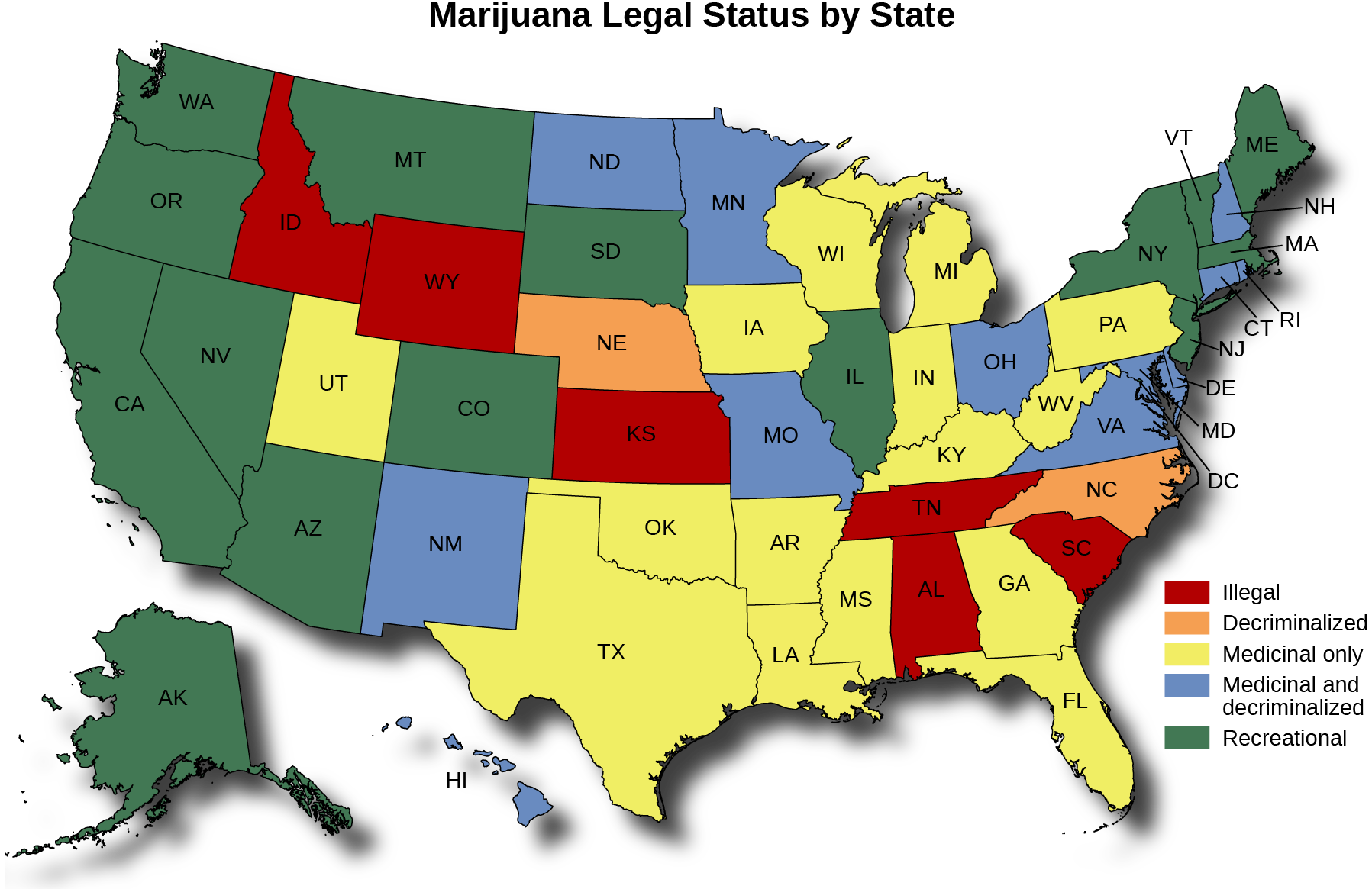

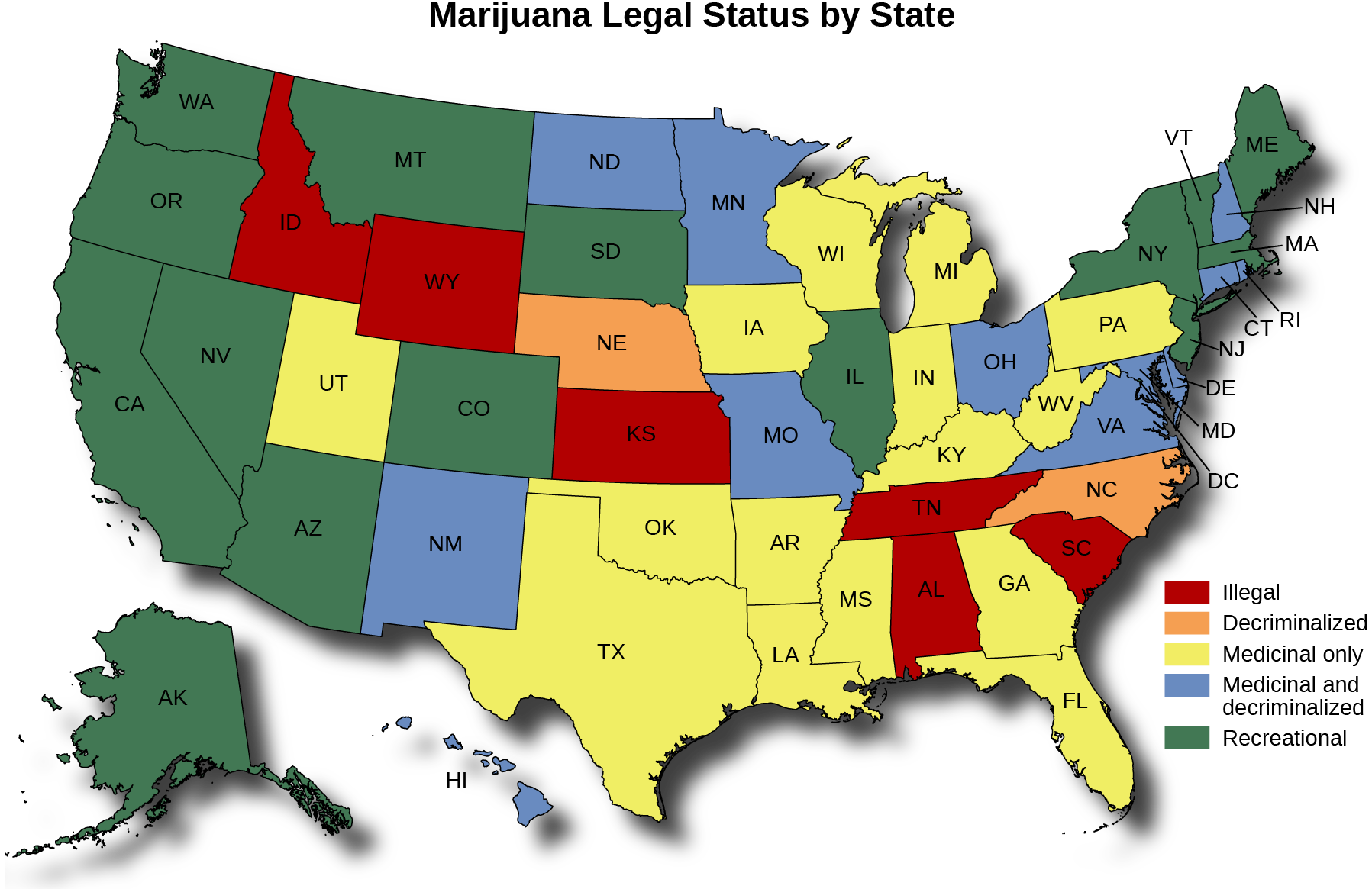

For example, a person over the age of twenty-one may legally buy marijuana for recreational use in sixteen states and for medicinal purposes in more than 80 percent of the country, but could face charges—and time in court—for possession in a neighboring state where marijuana use is not legal. Under federal law, too, marijuana is still regulated as a Schedule 1 (most dangerous) drug, and federal authorities often find themselves pitted against states that have legalized it. Such differences can lead, somewhat ironically, to arrests and federal criminal charges for people who have marijuana in states where it is legal, or to federal raids on growers and dispensaries that would otherwise be operating legally under their state’s law.

Differences among the states have also prompted a number of lawsuits against states with legalized marijuana, as people opposed to those state laws seek relief from (none other than) the courts. They want the courts to resolve the issue, which has left in its wake contradictions and conflicts between states that have legalized marijuana and those that have not, as well as conflicts between states and the national government. These lawsuits include at least one filed by the states of Nebraska and Oklahoma against Colorado. Citing concerns over cross-border trafficking, difficulties with law enforcement, and violations of the Constitution’s supremacy clause, Nebraska and Oklahoma have petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene and rule on the legality of Colorado’s marijuana law, hoping to get it overturned. [8] The Supreme Court has yet to take up the case.

How do you think differences among the states and differences between federal and state law regarding marijuana use can affect the way a person is treated in court? What, if anything, should be done to rectify the disparities in application of the law across the nation?

Where you are physically located can affect not only what is allowable and what is not, but also how cases are judged. For decades, political scientists have confirmed that political culture affects the operation of government institutions, and when we add to that the differing political interests and cultures at work within each state, we end up with court systems that vary greatly in their judicial and decision-making processes. [9] Each state court system operates with its own individual set of biases. People with varying interests, ideologies, behaviors, and attitudes run the disparate legal systems, so the results they produce are not always the same. Moreover, the selection method for judges at the state and local level varies. In some states, judges are elected rather than appointed, which can affect their rulings.

Just as the laws vary across the states, so do judicial rulings and interpretations, and the judges who make them. That means there may not be uniform application of the law—even of the same law—nationwide. We are somewhat bound by geography and do not always have the luxury of picking and choosing the venue for our particular case. So, while having such a decentralized and varied set of judicial operations affects the kinds of cases that make it to the courts and gives citizens alternate locations to get their case heard, it may also lead to disparities in the way they are treated once they get there.

See the Chapter 13.2 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary , and some review questions to check your knowledge.

the division of the courts into two separate systems, one federal and one state, with each of the fifty states having its own courts

× Close definitionthe level of court in which a case starts or is first tried

× Close definitiona court that reviews cases already decided by a lower or trial court and that may change the lower court’s decision

× Close definitiona law that prohibits actions that could harm or endanger others, and establishes punishment for those actions

× Close definitiona non-criminal law defining private rights and remedies

× Close definitionThe Dual Court System Copyright © 2022 by Lumen Learning and OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.